Graeme hopped on the wheels and pedalled away from his chasers. But there was one thing he could never effectively pedal away from – those dark episodes of feeling really low, later diagnosed as depression. But cycling, in a way, helped. As Graeme once said, he wasn’t a ‘racer at heart’ but joining a local cycling club dragged him into racing.

Shortly after leaving school, Graeme and his friend opened a bike shop. Unfortunately, this happened at the beginning of the 90s in Scotland, the era of economic recession. The shop quickly got in trouble, leaving Graeme indebted and depressed. In his words, two options seemed to be the solution: fight or flight. Luckily, he decided to go with the former one and he did it with style.

The Old Faithful

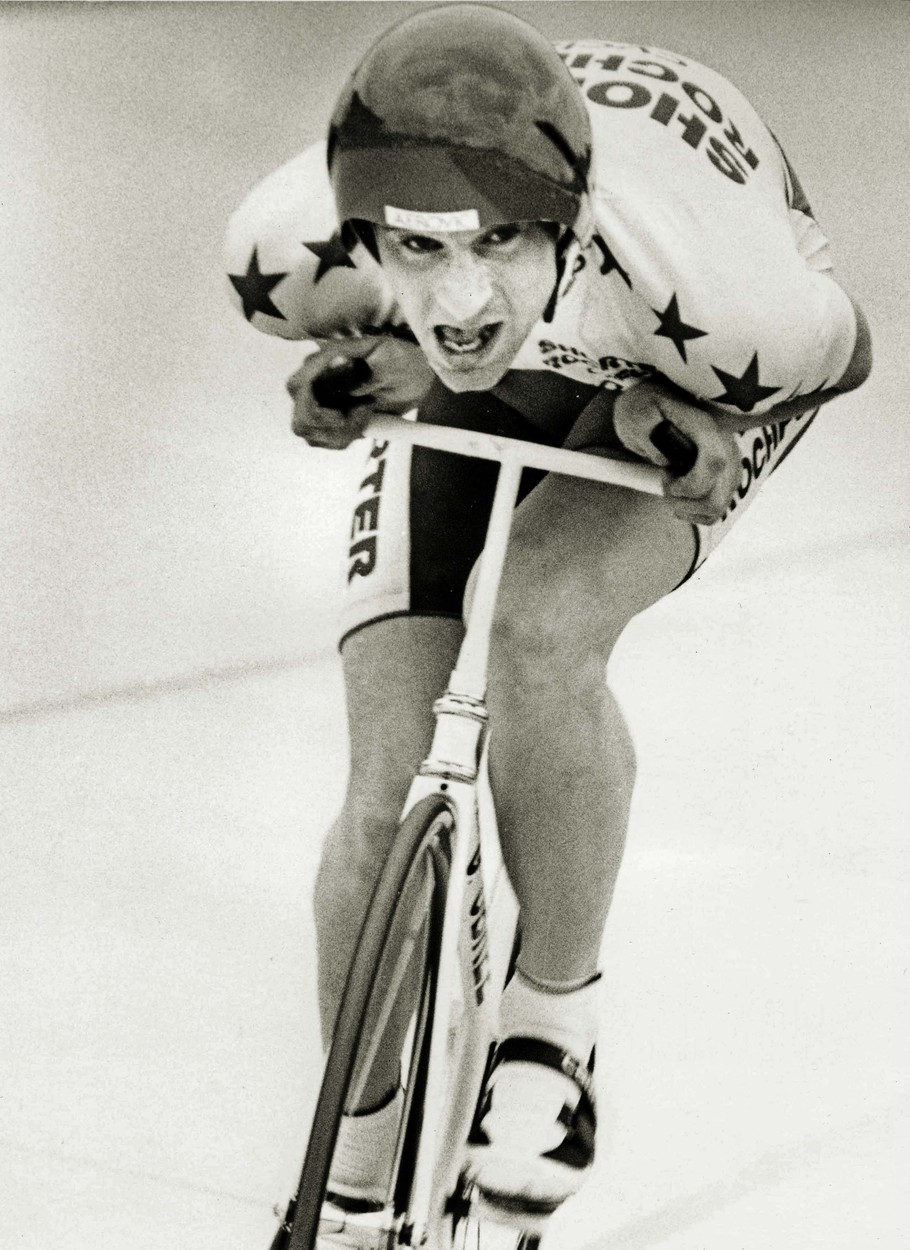

Graeme built his own bike, using spare parts from bike shops and a feature that raised many eyebrows: pieces of an old washing machine. The final design of the bike, named ‘the Old Faithful’, fit Obree’s unique cycling style called the ‘tuck’: he was riding in a position crouched over the handlebars with arms tucked into his sides. Obree believed this position, similar to one of a skier, was more natural and highly aerodynamic.

In July 1993, Graeme arrived in Norway with the Old Faithful and one goal: to break Moser’s nine-years-old standing record. But a twist happened to his original plan – when seeing the bizarre vehicle, his team convinced him to ride a replica bicycle; one he’s never ridden before. Obree yielded to the pressure, hopped on the replica, started pedalling and lost by nearly a kilometre.

He did not break the world record but set a world sea-level record so the viewers approached him with congratulations anyway. That moment prompted Graeme’s determination: he would give it one more shot. After all, he booked the stadium for 24 hours.

The next morning, Obree arrived at the stadium 5 minutes prior to his second record attempt. The night before, he would drink a lot of pints of water to keep him waking up every few hours. Any time he would get up and go to the lavatory, he would stretch his legs. With this kind of training after the exhausting first ride, Graeme and the Old Faithful conquered the deserted velodrome. For a bit, it seemed the UCI members won’t show up at all. In all fairness, who could blame them, given that it takes at least a couple of days for most riders to recover from a world record attempt. But finally, they did arrive. On 17 July 1993, The Flying Scotsman, as he was nicknamed, set a new world hour record of 51.596 km.

The record lasted for less than a week: on 23rd July, Chris Boardman, Obree’s keen rival, overcame his achievement with 51.864 kilometres. The rivalry got even juicier when Graeme beat Boardman at the world pursuit championship and re-claimed the champion title. While the two cyclists had great respect towards each other, the UCI did not hold such favourable feelings towards Obree.

The Battle with Depression

In 1994, the UCI changed the rules of the world championship, which effectively banned Obree’s style of riding. That event took place only a day before the championship race; Graeme was instructed to change his style but he respectfully declined, rode in his own unique way and kept pedalling even after the waving of the red flag, signalling his disqualification from the race.

The inventive rider adopted a new position, called the Superman, in 1995. Shortly after, the UCI banned that one as well. And yet another mishap was to follow. In 1995, Graeme’s brother died in a car crash. After that, it became harder and harder to concentrate on cycling. The Flying Scotsman was no longer flying – now he was drowning in alcoholism, trying to find a way to cope with his newly-diagnosed bipolar disorder.

When he definitively retired from international cycling, Graeme’s illness took over his life. It took years of alcoholism, two suicide attempts, counselling, and then a memoir, the Flying Scotsman, published in 2004 for Obree to come back to terms with his life.

In 2006, Obree’s memoir got a movie remake. Five years later, the Flying Scotsman revealed one important feature of his life – his homosexuality. Being raised in a conservative town of 70s Scotland, opening himself about being gay and coming out publicly was something unimaginable. However, Graeme managed to achieve this feat as well.

The story of Graeme Obree is not only one of great sportive achievements but it is truly compelling in its human part. These days, according to himself, he’s cycling a bit, writing some, living for now.